When David S. Ward’s “Major League” slid into multiplexes on April 7, 1989, many people viewed it as a professional baseball clone of the minor leagues’ “Bull Durham.” A savvy veteran receiver (Tom Berenger) with knee problems facing the barrel of a forced retirement? Check. A rookie pitcher (Charlie Sheen) with a flamethrower for an arm and no semblance of control? Check. A superstitious slugger (Dennis Haysbert) who demands to sacrifice a live chicken to get him out of a bad situation? Check.

The very existence of these familiar elements was enough for many domestic critics to dismiss “Major League” as a farcical comedy (Roger Ebert, who reviewed almost everything, ignored it completely). Moviegoers disagreed. The film grossed $50 million in the United States on an $11 million budget and earned an A-CinemaScore before becoming a home video/pay cable sensation. By the time the next baseball season rolled around, “Major League” was considered a standout, quirky classic about America’s pastime (it’s one of the 30 best baseball movies of all time according to /Film).

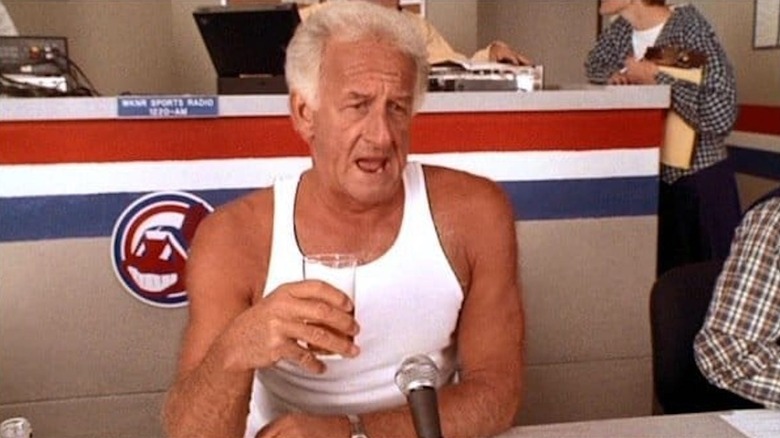

And it never would have happened if Ward hadn’t hired Bob Uecker to play Harry Doyle, the long-suffering, heavy-drinking man.

The only people who didn’t consider Uecker perfect casting as the radio announcer for the team then known as the Cleveland Indians (the organization changed its name to the Guardians in 2021) were Milwaukee fans Brewers, who were listening to “Mr. Baseball” has been calling their team’s games since 1971. But the former professional baseball player who once shared a dugout with Milwaukee Braves greats Hank Aaron and Warren Spahn was bigger than the city and more than just a celebrity sportsman when he took on the role of Doyle. He was the star of. many Miller Lite advertisements in the 1980s, and starred as television’s beloved father, George Owens, on the long-running ABC sitcom “Mr. Belvedere.” He was also featured on “The Tonight Show Starring Johnny Carson,” where he built his reputation for being quick with the perfect quip.

There was nothing surprising about Uecker stealing scene after scene in “Major League,” which may be why so many critics took the film for granted.

Bob Uecker was a poet of Midwestern sports misery

The “Major League” hook is as familiar as the aforementioned gags. Margaret Whitton stars as a Las Vegas showgirl who inherits the notoriously lousy Cleveland baseball franchise from her late husband. Having no love for the depressed Midwestern town on Lake Erie or its notoriously harsh winters, she forces the team’s front office to assemble a team of no-goods and has-beens whose poor performance will torpedo attendance and will allow him to move the organization to Miami. Basically, it’s “The Bad News Bears” with higher stakes. Predictably, this team of losers will come together out of a sense of pride and find themselves in a winner-take-all game with their arch-rivals (in this case, the New York Yankees).

“Major League” works wonderfully as a formulaic comedy about last-chance misfits, but even with top-notch performances from the entire ensemble, it would play like a cookie-cutter studio programmer without Uecker. Although Ward does a pretty solid job of conveying how unhappy it was to be a Cleveland baseball fan in the 1980s (the opening credits to Randy Newman’s “Burn On” are extremely effective), the sense of the gallows humor that allows the diehards to survive season after season, the heartbreak and futility shine through loud and clear when Doyle and his colorless man Monte are introduced during the opening day’s match. Uecker may be from Milwaukee, but he’s been around the game long enough to know that special quality of self-deprecating malaise that’s passed down through generations in Cleveland. And in his first scene, he makes sure every single person in the audience feels like they’ve ruined the trade of Rocky Colavito since they were born.

Harry Doyle lived just a little outside the truth

Uecker’s Doyle is a liar by necessity. On the outside, he is a spirited man who leads the game with eloquence and, despite his who knows how many years in the stand, a convincing capacity for surprise. A line drive to the deep center always has that mystery of distance to it. At least that would be the case if someone in this bad iteration of the Cleveland club could put enough wood on the ball.

Instead, Doyle must find fierce poetry in the first at-bat of Willie Mays Hays (Wesley Snipes), a total unknown who inexplicably turns an accidental dribbler at second base into a single. “Hey, here’s a hot shot to the hole,” Doyle exclaims as the defender charges the weakly hit ball. When Hays makes the throw, Doyle, out of breath, adds some color BS to the game by saying, “Hey, give Rudy credit for sacrificing his body on that racket. This guy has a family to think about.”

It’s going to be that kind of season for Doyle because it’s always been that kind of season. But he will make it seem like professional baseball is played here because his salary demands it. How does he cope with the horror? By pouring several fingers of Jack Daniels into a paper cup and lengthening further. Doyle is dying inside, but he’ll never let his ever-dwindling group of listeners know it.

Uecker’s best moment comes later in this game when he faces the roaming terror of Sheen’s Ricky “Wild Thing” Vaughn fastball. When the rookie pitcher’s first offering strays beyond the reach of Berenger’s Jake Taylor, Doyle utters the film’s most quoted line: “Juuuuust a little outside.” It’s a huge laugh line that drowns out the even funnier sequel “He tried the turn and missed.”

36 years later, sports commentators of all stripes still quote or paraphrase Doyle – and Uecker in general. But you can only get away with this kind of clever lie if you are the eyes of your listeners. It’s a dying skill, one that was never shared with sports fans before “Major League.” Doyle was an incorrigible fabulist for the stupid faithful. There is nobility in loving a team that gives you nothing but grief and believing that everything will work out when it never does. Bob Uecker, who died today at the age of 90, encouraged us to believe it because, deep down, I think he believed it too.