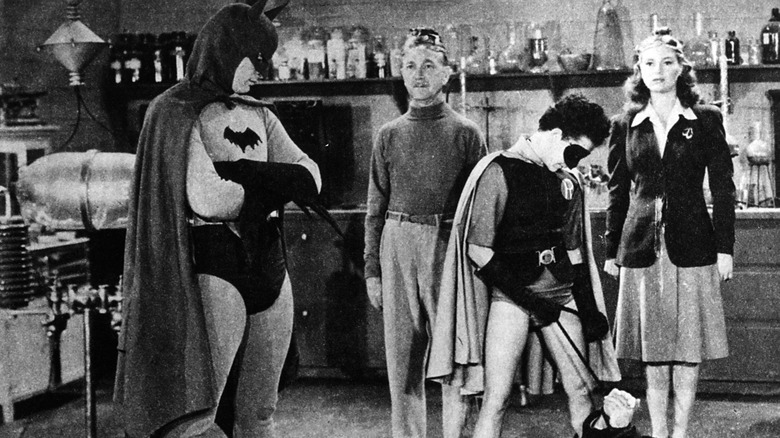

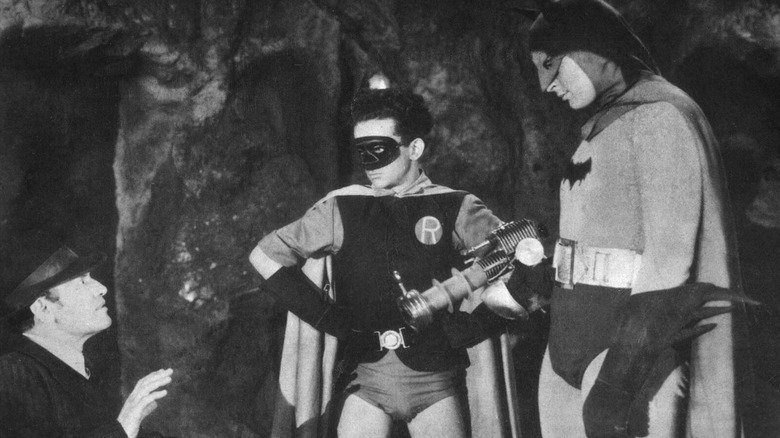

When most people think of the first days of Dark Knight live, they think of the television series Adam West and Burt Ward (and an accompaniment film) from the 1960s. This is understandable given its cultural impact and its lasting heritage, but the West Show was not the first time that Batman was brought from the comic strip page to the screen. In 1943, only four years after the character’s comic beginnings in “Detective Comics # 27” from 1939, Columbia Pictures produced and published a series of theatrical series with Lewis Wilson like Caped Crusader and Douglas Croft like Robin, with William Austin playing Alfred.

Released in 15 weekly payments, these series actually contributed to what later became key aspects of the franchise, in particular by transforming the batcave of a simple tunnel under Wayne Manor to a complete underground hiding place. At the same time, however, the ’43 adaptation has changed a lot compared to the original comics, transforming Batman into an American army agent and an anti-Japanese propaganda voice during the Second World War.

Yes, you read that right. Batman does not fight the Joker or Le Penguin in the series of 1943. Instead, he faces Dr. Daka, a discord of ethical brain sowing in Gotham under the direct orders of the Japanese government. Naturally, the character is played by J. Carrol Naish, a non -Japanese actor. These aspects of the series make it difficult to come back, to say the least, and his representation of Batman himself has trouble resisting those of the first years of comics. That said, the series remain a curious case study in American propaganda at the time, as well as one of the first adaptations of live superheroes never produced.

What’s going on in the 1943 Serials Batman?

A total of about three and a half hours in 15 episodes, the 1943 “Batman” series followed Bruce Wayne and Dick Grayson as they thwart various plans of Dr. Daka. These involve creating mental control devices that transform involuntary prisoners into enslaved zombies and try to use a powerful shelving pistol to threaten Gotham. Bruce also flirts with Love Interest Linda Page (Shirley Patterson), whose uncle Martin is kidnapped very early as part of the Daka plan.

The most entertaining part of the series today is certainly the action scenes, which derive at least a little charm from their early Hollywood stagication. The car prosecutions, the fist fights above large buildings, and other sets all bear the Campy style of the time, and it is sometimes to their advantage, because the real narrative material which supports the action varies from the hollow to extremely racist.

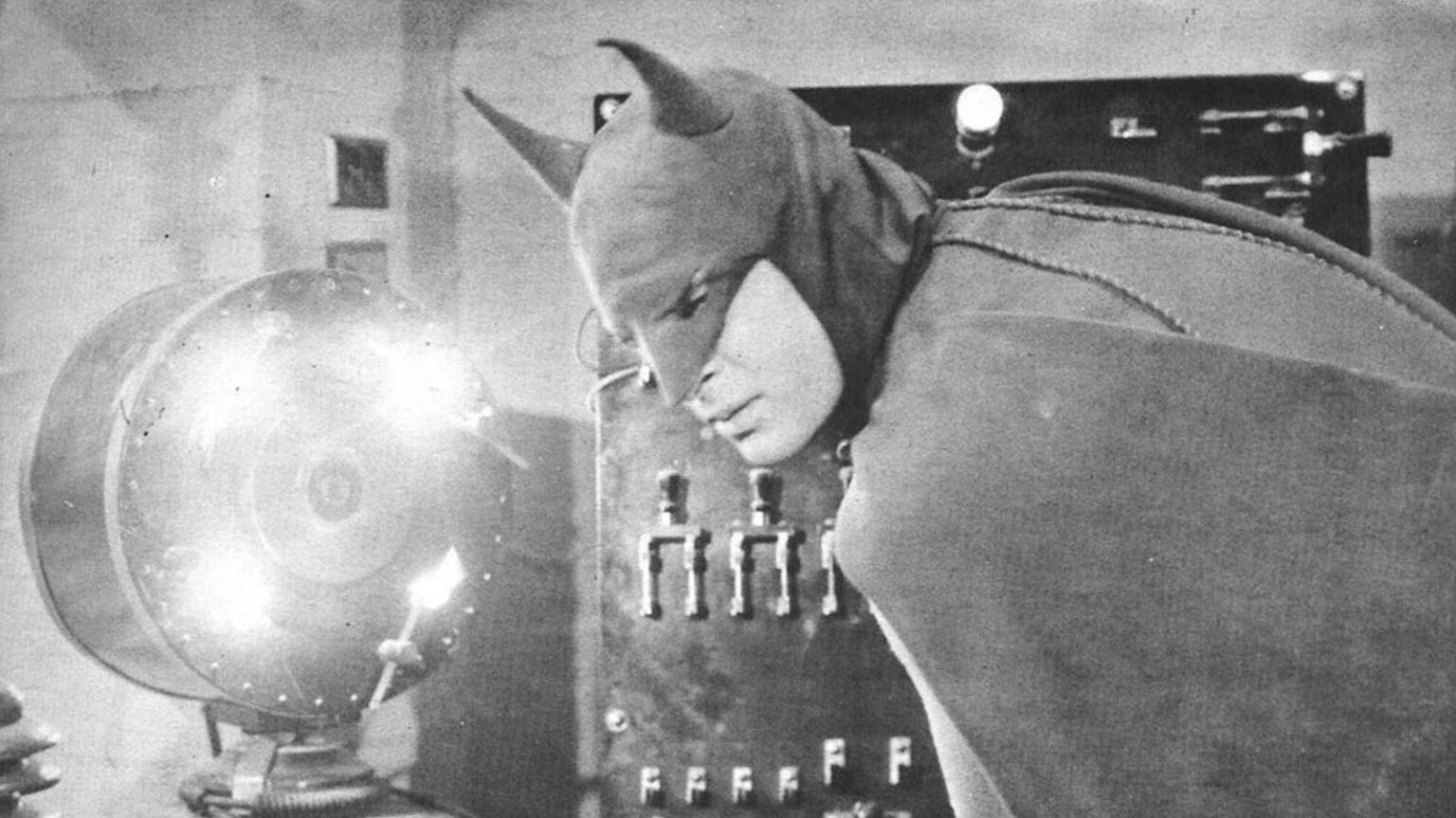

In terms of aesthetics, it is in fact a decent interpretation of Batman, given the short time since the character made his debut with DC Comics. It wears a cheap but relatively precise version of the character black and gray gray of the character, and although Robin is a little older than in the comics, his costume is quite precise (although black and white certainly moult). Meanwhile, the Batcave is an almost claustrophobic set with some hilarious “bats” effects sprinkled to make good measure. But even in its most silly moments, you can see part of the visual influence on subsequent adaptations – especially the series and the film Adam West “Batman”.

The 1943 Batman series actually very influential

You can trace a fairly direct line of the style and martons tone of the 1943 “Batman” series intentionally Campy from the 1966 television series with Adam West and Burt Ward. And it is not a coincidence. In 1965, just a year before the much more famous adaptation on the screen, the black and white series were reissued in a unique and complete story under the new name, “an evening with Batman and Robin”. The Cartoony style – already apparent two decades later – helped him gain a renewed interest and a new audience. It is therefore not surprising that the series of the 60s intentionally made things as ridiculous and stupid as possible, playing on this style.

That said, the main propagandist elements of the 43 series make them impossible to adopt fully within the framework of the biggest myth in Batman. A narrator tells us very early that Batman and Robin – who, once again, work as a superhero under “Special Assignment of Uncle Sam”, according to Bruce – “represent young Americans who love their country and are happy to fight for that”. The same disembodied voice informs viewers as when confronted with enemies from America, “Batman and Robin are ready to fight them until death”. The writing relating to Dr. Daka and the largest Japanese land is much more blatant.

All in all, however, there are much better Batman films. I would even go with the George Clooney version instead.