Warning: This story contains descriptions of sexual abuse

It was 8:25 p.m. on a Monday evening in November 2020 when Caroline Darian received the call that changed everything.

On the other end of the line was his mother, Gisèle Pelicot.

“She told me that she had discovered that morning that [my father] Dominique had been drugging her for about 10 years so different men could rape her,” Darian recalled in an interview with Emma Barnett of BBC Radio 4’s Today show.

“At that moment, I lost what was a normal life,” says Darian, now 46 years old.

“I remember that I screamed, cried, I even insulted him,” she says. “It was like an earthquake. A tsunami.”

Dominique Pelicot was sentenced to 20 years in prison following a historic three and a half month trial in December.

More than four years later, Darian says his father “should die in prison.”

Fifty men that Dominique Pelicot had recruited online to come and rape and sexually assault his unconscious wife Gisèle were also sent to prison.

He was arrested by police after upskirting in a supermarket, leading investigators to take a closer look at him. On the laptop and phones of this seemingly harmless retired grandfather, they found thousands of videos and photos of his visibly unconscious wife Gisèle being raped by strangers.

In addition to putting the issues of rape and gender-based violence in the spotlight, the trial also highlighted the little-known problem of chemical submission – drug-facilitated assault.

Caroline Darian has dedicated her life to fighting chemical submission, which is considered underreported because the majority of victims have no memory of the assaults and may not even realize they were drugged.

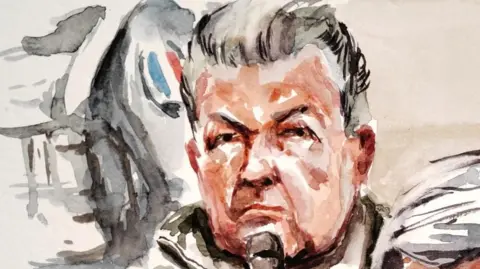

Jeff Overs/BBC

Jeff Overs/BBCDarian wants the voices of abused women to be heard

In the days following Gisèle’s fateful call, Darian and his brothers, Florian and David, traveled to the south of France, where their parents lived, to support their mother as she learned that – as the Darian says now – her husband was “one of the worst sexual predators of the last 20 or 30 years.”

Shortly after, Darian herself was called by the police – and her world was shattered again.

He was shown two photos found on his father’s laptop. They showed an unconscious woman lying on a bed, wearing only a T-shirt and underwear.

At first, she couldn’t tell that this woman was her. “I experienced a dissociation effect. I had difficulty recognizing myself from the start,” she says.

“Then the policeman said, ‘Look, you have the same brown mark on your cheek… it’s you.’ I then looked at these two photos differently… I was lying on my left side like my mother, in all her photos.”

Darian says she’s convinced her father also abused and raped her — something he’s always denied, although he’s offered conflicting explanations for the photos.

“I know he drugged me, probably for sexual abuse. But I have no proof,” she says.

Unlike his mother’s case, there is no evidence of what Pelicot may have done to Darian.

“And this is the case for how many victims? We don’t believe them because there is no proof. They are not listened to, not supported,” she said.

Shortly after his father’s crimes came to light, Darian wrote a book.

I’ll Never Call Him Dad Again explores his family’s trauma.

He also delves into the issue of chemical submission, in which medications typically used “come from the family medicine cabinet.”

“Painkillers, sedatives. They’re medications,” Darian said. As is the case with nearly half of chemical submission victims, she knew her attacker: the danger, she said, “comes from within.”

She says that amid the trauma of discovering she had been raped more than 200 times by different people, her mother Gisèle struggled to accept that her husband had also assaulted their daughter.

“For a mother, it’s difficult to integrate all of this at once,” she says.

However, when Gisèle decides to open the trial to the public and the media in order to denounce what her husband did to her and dozens of men, mother and daughter agree: “I knew we had experienced something …horrible, but that we must get through this with dignity and strength.”

Reuters

ReutersNow Darian must figure out how to live knowing that she is both the daughter of the executioner and the victim – what she calls “a terrible burden.”

She is now unable to think back to her childhood with the man she calls Dominique, only occasionally resuming the habit of calling him her father.

“When I look back, I don’t really remember the father I thought he was. I look directly at the criminal, the sex criminal that he is,” she says.

“But I have his DNA and the main reason why I am so committed to invisible victims is also for me a way of putting a real distance with this guy,” she explains to Emma Barnett. “I’m totally different from Dominique.”

Darian adds that she doesn’t know if her father was a “monster,” as some have called him. “He knew exactly what he was doing and he’s not sick,” she said.

“He’s a dangerous man. He has no way out. No way.”

It will be years before Dominique Pelicot, 72, can benefit from parole. It is therefore possible that he will never see his family again.

Meanwhile, the Pélicots are rebuilding. Gisèle, says Darian, is exhausted by the trial, but also “in recovery… She is doing well.”

Reuters

ReutersAs for Darian, the only issue he cares about now is raising awareness about chemical submission – and better educating children about sexual abuse.

She draws her strength from her husband, her brothers and her 10-year-old son, her “adorable son,” she says with a smile, her voice full of affection.

The events that unfolded on that November day made her who she is today, Darian said.

Today, this woman whose life was destroyed by a tsunami one November night is only trying to look forward.

“You can watch the full interview ‘Pelicot Trial – The Girl’s Story’ – Monday at 7pm on BBC 2 or on iPlayer. If you have been affected by some of the issues raised in this film, details about the Help and support are available at bbc.co.uk/actionline’.